Golf courses take up an extraordinary amount of land.

Together, London’s 95 courses cover an area larger than the borough of Brent. While it’s true that golfers come from across the demographic and socio-economic spectrum, the reality is that the protocols of golf itself severely limit how many people can make use of this open space at any one time.

Whichever way you look at it, in a congested city, golf does not represent an equitable use of precious land.

Do we need so many golf courses in London? And if we don’t, what else might we do with them?

Building on our previous research—which investigated the quantity, size, and ownership of the city’s golf courses—we’ve now taken a look at how these spaces might be used to better serve a larger proportion of Londoners.

Around 40% of London’s golf courses are owned by the boroughs in which they are located. Many of these councils are struggling with profound levels of housing need, not least homelessness and overcrowding, together with a rapidly expanding disparity between those in housing comfort, and those in distress.

The success of every planning authority in building homes (in London, represented by each of the 32 boroughs, the City Corporation, and two development corporations) is measured by a Housing Delivery Test; a government calculation which assesses homes delivered against overall housing need.

In the period leading up the 2021, the four worst-performing boroughs in London were Enfield (67%), Barking & Dagenham (66%), Havering (46%) and Kensington & Chelsea (43%).

As a result of their failure to deliver enough homes, each authority is now subject to what’s known as a “presumption in favour of sustainable development”, as determined by the National Planning Policy Framework – the most severe of the penalties available.

London’s 95 golf courses are distributed across 21—mainly suburban—boroughs. That’s around one course for 95,000 residents. Neither Kensington & Chelsea, nor Barking & Dagenham, have any golf courses within their boundaries. Enfield has seven courses (that’s one for every 48,000 residents) and Havering has nine (one course for every 29,000 people).

All of Havering’s courses are located within the green belt. In Enfield, just three are. The remainder are protected by virtue of their designation as “Metropolitan Open Land”, a planning policy unique to London.

The justification for blanket restrictions on development of golf courses that fall within this policy is, at best, dubious. Few courses meet the stringent requirements established by the policy: they are neither accessible, nor ecologically important. It is our belief that responsible development, accompanied by landscape and biodiversity improvements, is compatible with this designation, and far better serves the needs of Londoners.

With this in mind, we have identified the London Borough of Enfield as an area of focus. Within it are seven courses, four of which are owned by the council. Only one of these is located within Metropolitan Open Land: Enfield Golf Course.

The Enfield Context

Housing delivery is more than just a numbers game. Whilst we clearly need many more homes to address London’s housing shortage, every one we build should be affordable to heat and light, comfortable and delightful to inhabit, and enable every resident to live a healthy and fulfilling life. New development should also make a positive contribution to the local community.

A lack of affordable, secure housing is clearly a pressing social challenge for Enfield, but there are also other opportunities that can be exploited here too. All new development must achieve carbon net-zero in both construction and use. It must promote active modes of transport, and avoid a reliance on private vehicle ownership through the creation of walking and cycling routes. There should be enhancements to community wellbeing, and an improvement in ecology, biodiversity and urban greening which integrate with surrounding landscape. New social infrastructure should be provided for the wider suburban area, including retail uses, leisure activities, education and zero-mile food production, knitting the neighbourhood back together.

All of these things are possible if we choose to develop golf courses in a responsible and creative way.

Below, we’ll show how.

Enfield Golf Course

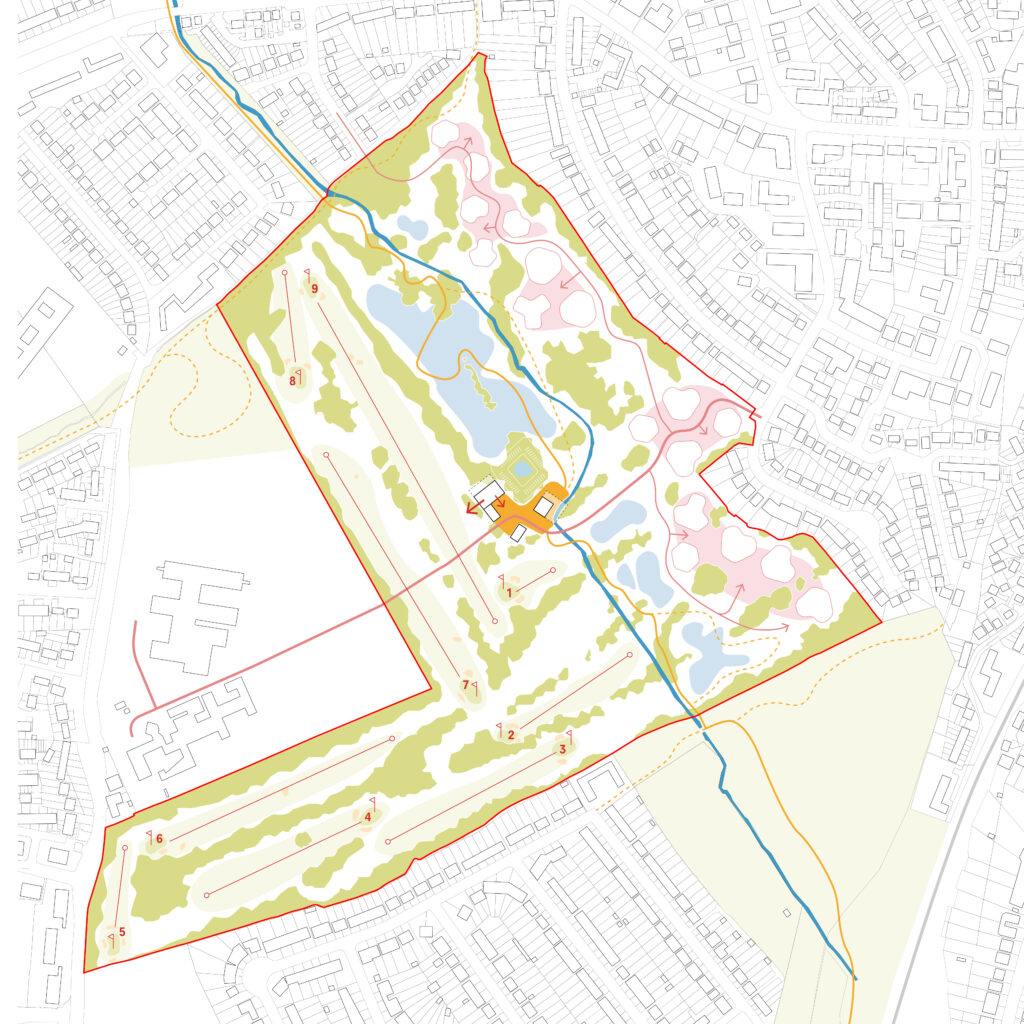

Enfield golf course lies in the heart of the borough, a few minutes’ walk from the town centre (and conveniently close to two other courses).

At 39ha, it takes up a large area of land, and acts as an impenetrable barrier between Oakwood and Enfield town centre.

We believe that this course could be developed to unlock new homes and social infrastructure to serve the existing community around it—while also retaining nine holes so that existing members still have somewhere to play.

This includes a new east-west pedestrian and cycle link helps knit the neighbourhood together, providing existing residents with new and enhanced access to schools, natural landscapes and local amenities.

We have exploited the low-lying areas of the existing course, and the stream that runs through it, to introduce biodiverse wetlands and mitigate localised flooding. This enhances the green chain connections to other nearby natural assets. The loss of trees has been minimised by locating new development on fairways and putting greens where biodiversity is most limited.

Most importantly, we have found space for 650 homes within a series of efficient, low- to mid-rise villa blocks, set within a green landscape, and linked by cycle and walking routes and close to public transport. These homes are sustainable, efficient, and varied in size to provide a mix of homes that meets local need. Allotments and growing areas allow for zero-mile food production. Minimal parking is provided, reducing car dependency, and encouraging active travel.

New wetlands include nature trails and walking routes, with community facilities placed in the centre of rewilded parkland providing teaching areas for local schools. Elsewhere within the development are a new health centre, gym, pharmacy, mobility hub, heritage centre and café. And a large golf course.

On this page we’ve given an indication of what this might look like. This is not intended to be a fully-resolved masterplan, but simply an aspirational vision for how we might accomplish a heathier, more equitable city.