This article is by Tim Riley

A founding director of RCKa, and with experience in delivering large scale regeneration projects and strategic masterplanning, Tim is responsible for delivering the practice’s residential work. He also sits on design review panels for the London Borough of Harrow, Hounslow – and is chair of Hertfordshire’s Design Review Panel.

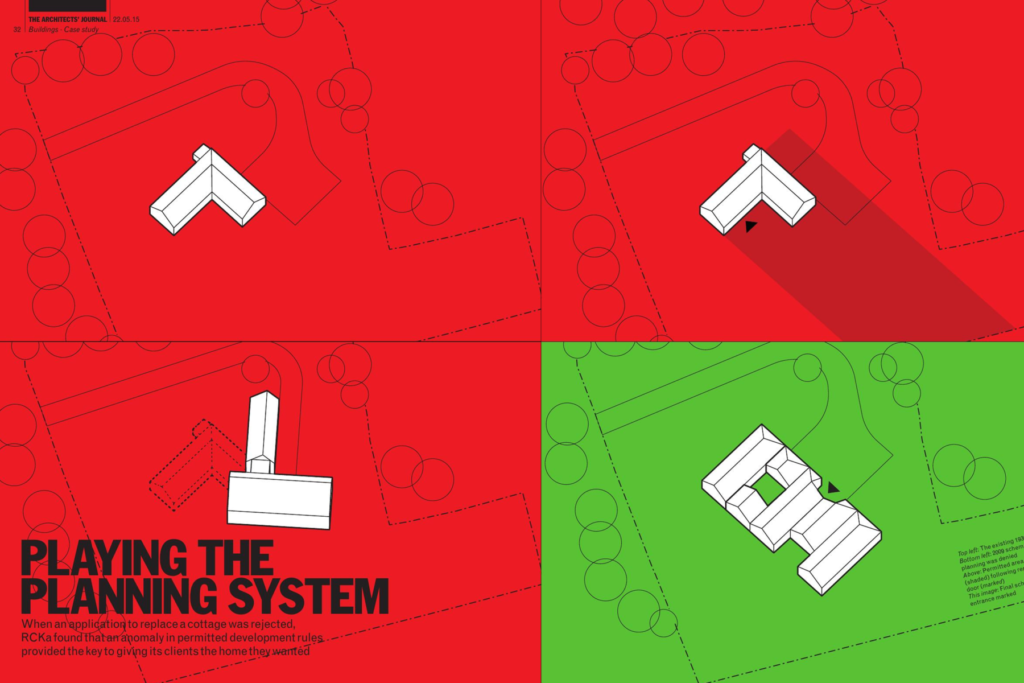

When an application to replace a cottage was rejected, RCKa found that an anomaly in permitted development rules provided the key to giving its clients the home they wanted.

In late 2008 the government fundamentally changed the rules governing what adaptations homeowners could make to their properties without obtaining planning permission. This adjustment to existing legislation – known as ‘permitted development’ – was aimed at reducing the number of hoops through which property owners had to jump when making straightforward alterations where these houses conformed to certain stereotypical arrangements: the Victorian terraced house; the 1930s suburban semi; the 1980s detached executive home.

For less conventional dwellings that do not fit neatly into these categories, this has allowed architects to creatively interpret the regulations in order to unlock sites for development that had previously been refused planning permission.

In broad terms, permitted development provides a series of geometric rules governing how a property can be enlarged without planning permission, provided standard criteria are met. This ‘one size fits all’ approach serves the majority of people very well but, in certain cases, has led to unintended consequences.

In 2006 we were approached by a client who owned a single-storey wooden cottage in the centre of a half-acre plot of land deep within the West Sussex countryside. The land had been in the family for several generations and the house standing on the site had been built by the current owner’s grandfather in the early 1930s.

As the family expanded, it became apparent that this modest little cottage, which had played such an important role in the family’s history, was no longer suitable as a modern home. The client and her family decided they would like to invest in the site, and commissioned RCKa to design them a new house which would make the most of the site and their long-standing connection with the area.

In the years that had passed since the house was built, adjacent plots of land – many far smaller than their site – had been sold and redeveloped to provide much larger homes. The cottage was now dwarfed by larger houses on all sides.

And so, early in 2009, we submitted a planning application for a new home on the site of the cottage. Although larger in size, we had carefully designed the new house to minimise any visual impact on neighbours, concealing some accommodation below ground and using a slope on the site as well as rooms within the roof to ensure that the increase in size, as seen from the street, was negligible. The use of similar materials, details and form as the existing home helped to ensure the proposals remained sympathetic in scale and character to its surroundings.

Later that summer we received notice from the district council that our application had been refused. The apparent imposition of an arcane rule governing the allowable increase in footprint – not included within any planning policy but used by planning officers to determine acceptable dwelling sizes regardless of site area, context or need – meant our proposal was determined to be too large, despite the presence of considerably larger properties on adjacent, far smaller plots. Subsequent discussions with the planning department proved time-consuming and fruitless.

Returning to first principles, we decided to look again at how we might design a scheme that circumvented a dysfunctional planning system. It was then that we realised that the changes to the permitted development regulations, made at the end of the previous year, provided the key to unlocking the site and achieving the generous family home our client wanted. It would, however, involve a fundamental redesign in order to deliver a high-quality home that complied with the new rules.

While aimed primarily at owners of conventional houses, the wording of the new regulations presented far greater opportunity for creative interpretation compared with the legislation that preceded it – whether this was intentional or not.

The fundamental principle of permitted development is that it places restrictions on extensions to existing dwellings, whereas we had always assumed that we would be designing an entirely new home. We realised that, by retaining the cottage, we could apply a different set of regulations to achieve the client’s aims in the face of a resistant planning authority.

A close reading of the legislation revealed an anomaly in the definition of how the rules governing extensions are applied. It was clear that side and rear extensions to an existing property were restricted to 4m, while extensions at the front of any house facing the highway were prohibited. But what if the front of the house did not face the road? In this case an extension could be unlimited in its depth, provided it were no wider than the existing house. This was precisely the condition that applied to our site: repositioning the front door to face away from the road, rather than towards it, meant that we were able to expand the existing house back into the site almost without restriction.

With the parameters of the building defined, we began developing a new design that borrowed the form and finishes of the existing house in a modern manner. With no restrictions on the construction of a basement, we have introduced a lower ground floor level, with a sunken courtyard letting daylight into the spaces below, containing bedrooms and bathrooms. Open-plan living accommodation on the upper ground floor provides direct access to the gardens that surround the house.

Eaves and ridge lines match that of the original cottage, whereas the internal floor level is terraced to follow the landscape. With the extended building having such a deep plan, we investigated cutting holes from the permitted form to introduce courtyards, and these began to define the open-place space, orientate the building and introduce natural light into its depth.

It is endlessly frustrating that the planning system, which is specifically tasked with encouraging sustainable and responsible development, often seems to do the opposite. Instead of adopting an intelligence-led, bottom-up approach that responds to local needs and site-specific conditions, it becomes necessary to rely on national legislation in order to achieve high-quality and sustainable architecture that responds positively to the changing nature of our society. While the rules regarding permitted development were never intended to be exploited this way, this project shows that they can present an ideal challenge for motivated architects to unlock brownfield sites to deliver high-quality homes.